To The Dawn of Unix... and Beyond!

July 21, 2025

I took a time machine back to the dawn of Unix. To my surprise I found it all started with something the Bell Laboratories computer wonks cooked up for reports and legal documents. It grew rapidly into a philosophy for writing code.

They called it roff, as in Let me run-off a document for you.

It transformed plainly-typed text into something that you could feed into a type-setting machine. The result was professional-looking documents faster at less cost compared to sending typewriter paper to a printing company.

Today, the GNU Project supports an open-source program named GNU roff, or groff for short, that works like roff only better. It can be installed for free on just about any Unix-like computer, including Apple's Mac lineup.

People still use groff. It can typeset a whole book! Yet your Dear Diarist managed to go more than forty years without ever hearing of it. My loss.

Something I read a week ago mentioned groff in a way that piqued my interest. Within the week I learned how to use it. To give an example, I typeset this article as a PDF file that you can download.

The process renewed my appreciation and wonder for the special philosophy of Unix as it manifests in the open-source operating system called Linux. I list the main points this way:

- All data are text. That is to say, everything boils down to a series of numbers, one after another, like a stream.

- A program does three things:

- Receive text in.

- Do something with it.

- Send text out.

- Programs should be short, doing only one thing but doing it well.

- Process data through a series of short programs like beads on a string. Each program does its particular part of the work then sends its output into the next program. Unix calls such a string of beads a pipeline. Data flow through the series of programs like a pipe.

- Avoid re-writing programs once they are working well. Write a new, supplementary one instead. For example, suppose you want to add a new feature to a document. Write a new, short program to perform the step then add it to the pipeline.

The Bell Labs computer folks took that approach when their scientists wanted to include mathematical equations in their documents. They kept roff as it was but wrote a program called eqn to accept math expressions in a simple, typewritten form and change them into complex, rather arcane instructions telling roff how to render them. Instead of sending their text directly into roff the scientists would pass it through a pipeline: text ‑> eqn ‑> roff. Presto! Feature added.

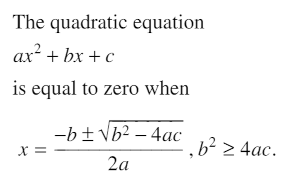

Math rendered by

eqn and groff

The text producing the output shown nearby was:

.LP

The quadratic equation

.LP

$ax sup 2 + bx + c$

.LP

is equal to zero when

.EQ

space 150

x = {-b +- sqrt { b sup 2 - 4ac } } over 2a

, b sup 2 >= 4ac.

.EN

As you can see, the Bell Labs scientists still had to learn a rudimentary kind of code, called markup, to place in their text document in order to obtain nice-looking math stuff from the typesetter. In fact, anyone using roff back then or groff today needs to learn some markup and to incorporate it into the text they write.

The Bell Labs originators of Unix wrote programs to edit text. They wrote a program called sed, short for stream editor, to automate wholesale changes to a text. Write some instructions (in text, of course) telling sed what changes to make. Run the text you want to revise through sed. It comes out changed.

They wrote a whole language, called Awk, to perform many other, different kinds of procedures based on instructions originally typed in plain text.

So, thanks to my time machine, this week I went back and learned to use sed and Awk.

Almost all coding done today follows a similar philosophy: type some text then feed the text into a pipeline of programs that do something useful with it.

One can automate almost anything about a computer by means of some text and a suitable pipeline of short, simple programs. Many of those programs have been around in Unix/Linux-Land for the past half of a century. We do not really need the latest-greatest vesion of Windows or Mac OS or Microsoft Office to perform serious work.

I returned from my time travel with an interesting question: which parts of a task should be automated, versus other, different parts that should be retained under the fingers of a human being? That, Dear Diary, is a different topic for another day.