To Read A Dictionary

May 31, 2025

To read a what? Dear Diarist, why? WHY?

I have been learning to write code in the C language to make lists. The technique allows a program to interact with data in a flexible way. When I say flexible, I mean not needing to know everything about the data ahead of time.

For exercise, I assigned myself to write a program that reads into memory all of the words in my laptop’s spell-checker dictionary.

Such a dictionary is merely a list of words. My program extracted 73,753 distinct words and stored them in memory. They ranged in length from one character (‘a’ and ‘I’) to 22 (‘counterrevolutionaries’).

Wow.

The C language looks rigid to a novice code writer. It imposes strong typing for variables. A variable is a container for one piece of information.

Strong typing means the code must not only assign a name for a variable but also indicate its size, which is the number of units of memory it will occupy. Each letter in an English word takes up one unit of memory.

Organizing the memory usage up-front, in the code, before the program runs, is called static memory management. Static means the program cannot change the size of a variable while it is running.

To store 73,753 words into memory statically would require separately writing 73,753 distinct variable names into the code. That much static can make a program-writer’s hair stand on end! It poses two challenges.

The first, obviously, is to make allowance for all those different word lengths without knowing in advance how many letters are in each word. The second challenge arises when the code writer does not even know in advance how many words the program will need to store!

The concept of a list gives a way to deal with this problem. In effect, a list becomes a variable for which the size need not be known in advance, and for which the size can be modified dynamically, meaning, while the program is running.

This old dog has been writing programs in C for ten years without using lists, because I did not understand them. Recently I decided it was time for Old Dog to learn new tricks. So I delved into lists.

The trick of lists is to pair each word from the dictionary with another thing: a so-called pointer that tells the program where to find another such pair. Each of these data pairs in the list points to the next. A single variable name, call it ‘wordList’ for example, need only contain a pointer to the first pair.

You can skip reading this box if you do not plan to write C code for lists any time soon. On the other hand, please do read it if you desire more detail on building a list to hold all the words in a dictionary.

For technical reasons, these “data pairs” of mine would not easily handle the situation where one member of the pair is a word that could have different lengths.

My solution was to save the words separately. It allows each word to take up only the number of memory units equal to the number of its letters, which we know is going to vary.

The C language gives us a way to do this so that we obtain a pointer to the word. Pointers are always the same size.

That way, all of the data pairs in my word-list become the same size because each data pair consists of a pointer to a word and a pointer to the next such pair in the list.

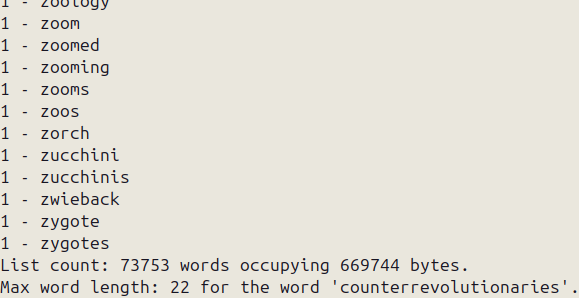

I wrote wordList into my code as a variable designed to point to a list of those word + pointer pairs, without needing to know how much memory it might require. The list proved able to contain 73,753 distinct, English words containing a total of 669,744 letters. Figure 1, below, shows a selection from the output.

Figure 1 Selected output from the program

Bringing all this information into the computer’s high-speed memory empowers a program to examine it very rapidly. In fact my program counted the words by stepping through the list, summing the sizes of the words as it went along.

So there I was, filled with the pride of new knowledge and strutting around the house, when Bride of Diarist asked, What would you use it for?

Er, um, ahh... Oh! I know! Crossword puzzles. Suppose you are looking for a five-letter word and you know the third letter is ‘j’. The program speeds through the list, almost instantly printing out the eleven (out of 73,753!) words matching the criteria.

Fun! A wacky guy could even write a line of friendly dialog for a play with some of them.

The scene is a picnic somewhere in Louisiana.

The host notices a guest in military uniform,

studying the selection of different mustards for a sandwich.

HOST: Enjoy Cajun dijon, Major Kojak!

Ha! said I. Try that without a whole dictionary in memory! She gave me one of Those Looks.

My dive into a dictionary was just an exercise to help me learn more about writing lists in C. More modern languages may support lists automatically; in C we have to write our own.

I would use lists mostly to solve problems, rather than to look up words. The dictionary project was just a key that I turned to unlock a big, new door in my mind for writing code in C.

Speaking of BIG, I found longer lists of words online. A Github page was making one available for download that claims to deliver more than 479,000 English words. Hmm...

. . .

Calm down, Code Diarist. Otherwise we might have to add your name to a certain list somewhere.